- Home

- McGilligan, Patrick

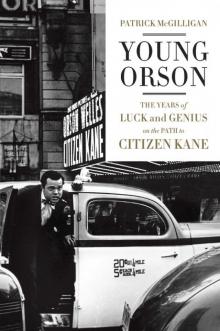

Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane

Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane Read online

DEDICATION

FOR BERTRAND TAVERNIER

EPIGRAPH

Everyone will always owe him everything.

—JEAN-LUC GODARD

CONTENTS

Dedication

Epigraph

I. BEFORE THE BEGINNING

CHAPTER 1 The Backstory to 1905

CHAPTER 2 1905–1915

II. ROSEBUDS

CHAPTER 3 1915–1921

CHAPTER 4 1922–1926

CHAPTER 5 1926–1929

CHAPTER 6 1929–1931

CHAPTER 7 1931–1932

CHAPTER 8 1932–1933

CHAPTER 9 1933–1934

III. TOMORROW AND TOMORROW AND TOMORROW

CHAPTER 10 1934–1935

CHAPTER 11 1936

CHAPTER 12 1936–1937

CHAPTER 13 1937–1938

CHAPTER 14 January–August 1938

CHAPTER 15 September–December 1938

CHAPTER 16 December 1938–July 1939

IV. SEVENTY YEARS IN A MAN’S LIFE

CHAPTER 17 July–December 1939

CHAPTER 18 November–December 1939

CHAPTER 19 February–May 1940

CHAPTER 20 June 1940

V. AFTER THE END

CHAPTER 21 October 10, 1985

Sources and Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Photographs

About the Author

Also by Patrick McGilligan

Credits

Copyright

About The Publisher

I

BEFORE THE BEGINNING

CHAPTER 1

The Backstory to 1905

The deep backstory of the most celebrated film ever made begins in the winter of 1871 at a boardinghouse in the fictional town of New Salem, Colorado. As the handwritten line of an unpublished reminiscence drifts by onscreen, the camera reveals “the white of a great field of snow,” according to the screenplay, and “in the same position as the last word” of the manuscript “appears the tiny figure of CHARLES FOSTER KANE, aged five.” The scene was shot on Stage 4 at RKO in Hollywood, and the snow was actually a carpet of crushed cornflakes. The artificiality worried the filmmaker, who knew that audiences familiar with cold winters might expect to see puffs of vapor when the characters breathed. But the young boy’s action diverts our attention. “He throws a snowball at the camera. It sails towards us and out of scene.”

Smack in the middle of the evocative “Snow Picture” passage in Bernard Herrmann’s score—a “lovely, very lyrical” musical phrase, in Peter Bogdanovich’s words—the filmmaker cuts the music abruptly just as five-year-old Charlie Kane’s snowball slams into the house.

“Typical radio device. We used to do that all the time,” Orson Welles explained to Bogdanovich.

The winters in Wisconsin could be as frigid as those in Colorado. But the white carpet had melted in the southeastern part of the state by May 6, 1915. The customary spring storms that pounded Wisconsin’s fifth-largest city had turned its streets into muddy rivers. It was a Thursday, and the rain had vanished for the weekend. Kenosha woke up to a morning cool, cloudy, and dry.

Anyone interested in the ongoing annihilation in the Dardanelles, the retreat in Hungary, or the ultimatums in Japan would have to turn to the inside pages of the Kenosha News. The front page was taken up with the boom in factory manpower; improvements on the north shore road; plans for the eightieth founders’ festival, including a baseball match pitting a local team against the Chicago Cubs; and the grand opening of a downtown beauty parlor promising facials, manicures, and electrolysis.

The southernmost Wisconsin city on the shore of Lake Michigan, Kenosha was no longer a Podunk. With a swelling population of twenty-six thousand, the city looked toward a bright future. Its size and attractions could never compare with those of other cities hugging the same Great Lake shoreline: Chicago, sixty-five miles south; or Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s largest city, forty miles north. But life was good in Kenosha. That spring, a forty-nine-pound sack of Gold Medal flour cost $1.95. A tailored woolen suit went for $16.50. A Ford roadster sold for $458, which included delivery and a $50 rebate.

The city theaters were booked for Mother’s Day, which was coming up on Sunday. The respectable Rhode Opera House, the largest theater in Kenosha, seating nearly one thousand, advertised the Western M’Liss starring Barbara Tennant. The New Majestic would show Thomas H. Ince’s version of Ferenc Molnár’s The Devil, a satire about a charming, debonair Devil who delights in fostering infidelity. This five-reeler was just the kind of sordid entertainment the Kenosha News complained about in its May 6 editorial, deriding moving pictures as “the people’s book” for impressionable youth who were abandoning healthful reading in favor of screen fare that glamorized sinful behavior.

The city’s only female public official, a member of the Kenosha School Board, led the ongoing civic crusade against these sordid moving pictures. In the early hours of May 6, she could be found in her home on the second floor of the two-story wood-frame house at 463½ Park Avenue in Library Park, a fashionable downtown area known for its massive churches, imposing brick mansions, and public commons, crowned by the Gilbert M. Simmons Memorial Library.

That wood-frame house on Park Avenue was neither architecturally distinguished nor luxurious, however, and, as the “½” in her address suggested, the school board official and her family were merely leasing the home’s upper floor. Although she and her husband were among Kenosha’s most prominent and admired citizens—appearing regularly in the newspaper’s society items—the couple prided themselves on their ties to ordinary people. The first female voted into a citywide office in Kenosha, she was not only a community activist and passionate suffragist, but an accomplished pianist and recitalist too. Her equally civic-minded husband, a founder of one of the city’s large metal and brass factories, was also an inventor who held a dozen patents.

Although the husband traveled frequently, he was at home on May 6, waiting with a cigar to celebrate the birth of the couple’s second child. The first child, a son born ten years earlier, was sequestered in his room under the eye of the family’s Irish live-in servant. The expectant mother’s attending physician, like many of Kenosha’s doctors, had earned his medical degree in Chicago from the homeopathic Hahnemann Medical College.

Another doctor in this unfolding saga, a family friend, was not in the house at the time of the baby’s delivery. Dr. Maurice A. Bernstein was an orthopedic surgeon, not an obstetrician, but in later years—after he outlived the school board official and her businessman-inventor husband—he would emerge as the chief chronicler of the boy’s birth, and other milestones of his early life.

Over the years Orson Welles took a lot of ribbing about having been born in Kenosha. He had to spell the humble city’s name for interviewers in the great metropolises of the world: New York, Los Angeles, Dublin, Paris, London, Rome, Madrid. At times he mocked and disparaged Kenosha, and he had his reasons. But he was also shaped by his roots, and no matter where he roamed he insisted in interviews that he was a proud “Middle Westerner.”

“I am almost belligerently Midwestern,” he wrote on one occasion, “and always a confirmed ‘badger.’ ” The badger was Wisconsin’s state animal and mascot.

According to Dr. Bernstein, when the baby was born, his mother noticed that his first cries mingled with the sound of factory whistles. The baby’s birth certificate notes the time as 7 A.M., when local workers began their typical ten-hour shifts—so this, at least, is plausi

ble. “The sounds of factory whistles are significant,” Bernstein quoted Mrs. Welles as saying. “They herald my baby into the world.” Her husband’s company employed hundreds of laborers, and Mrs. Welles sympathized with the workers.

Dr. Bernstein said later that the newborn entered the world with “a considerable growth of black hair on its head” and peculiarly slanted eyes that made him look Eskimo or Chinese. Since Bernstein lived in the neighborhood, he well may have seen the infant within hours or days of the birth. Bernstein said he noticed “a strange soberness in its countenance . . . when it looked into your face you felt uneasy as it if looked right through your soul.” Jotting notes years later for a book that he would never finish, Bernstein wrote that the child “looked as if it wakened from the sleep of a former existence.”

Perhaps more than anyone else, Dr. Bernstein was responsible for the idea that the boy was a wonder, special from birth. But even Orson Welles felt the doctor “gilded the lily rather thickly” in his mythmaking. Bernstein himself realized he was prone to exaggerate, and he could be very amusing on the subject. Writing to an RKO studio publicist in 1940, Bernstein claimed that within a day after his birth the baby “spoke his first words, and unlike other children who say the commonplace things like ‘Papa’ and ‘Mamma’ he said, ‘I am a genius.’ On May 8th, 9th, and 10th, 1915, little was heard about him in the press,” the doctor continued, “but on May 15th he seduced his first woman.”

Still, the baby was special from birth. Not every newborn in Kenosha was welcomed to the world on the front page of the local newspaper. But there it was, in the very next edition after his birth: hearty congratulations to the parents and the proclamation of his name, George Orson Welles.

The child wonder. The boy genius. The maker of Citizen Kane.

The words “genius” and “gene” share an etymology. In ancient Rome, the genius was the guiding deity of the family, or gens. The words derived from the Latin verb generare, to create. When individuals exhibited extraordinary traits that indicated the presence of the family’s guiding spirit, the word “genius” came to mean someone who was inspired or talented—suggesting that the creativity of a genius began with the qualities of his or her family. By that light, the lasting depth, complexity, and power of Citizen Kane might be traced to the filmmaker’s family. They launched a singular life story, one with the richness, layers, and texture of a novel.

The father of George Orson Welles was forty-two-year-old Richard Head Welles, known to all as Dick Welles. The boy’s mother was thirty-five-year-old Beatrice Ives Welles. Together Mr. and Mrs. Welles would carve the destiny of their second son, pointing him toward greatness from the cradle.

Beatrice Ives Welles had inherited a family legacy of artistry, spirituality, self-fulfillment, and civic-mindedness. The story of her Ives ancestors—dating back to seventeenth-century New England—reflected, and in some ways personified, the first years of American history.

In the early nineteenth century, one branch of the Ives family made its way to Oswego, New York, where J. C. Ives established himself as a builder of town walls, settlers’ stone residences, and lighthouses on Lake Ontario. His son John G. Ives traveled from Oswego south to Auburn, New York, to learn the jewelry trade, and then at age twenty-one he headed west to Springfield, Illinois. The year was 1839, and Springfield, settled as a trapping and trading outpost, had just been named the state capital. Ives and a fellow New Yorker, Isaac Curran, opened a watch, jewelry, and silverware store called Ives and Curran, on the west side of the Springfield public square.

In Springfield, Ives met Abigail Watson, whose English ancestors had traveled from New Jersey to Tennessee and Missouri before landing in Illinois. Abigail’s father, William Weldon Watson, lugged a soda fountain in a prairie schooner from Philadelphia to Nashville, using money from sales of the soda water (“to counteract the local whisky demon,” as his Nobel Prize–winning descendant James Watson put it) to build a church, establishing the first Baptist ministry west of the Appalachians. After his spouse died, Watson and his five children moved first to Saint Louis, then Springfield, where he remarried and opened a confectionery store. His oldest girl, Abigail, was twenty years of age when she married John G. Ives in Springfield in 1843.

Springfield was also home to a prairie lawyer named Abraham Lincoln, and the place was growing into a stronghold of liberal opinion about slavery, the gold standard, and high tariffs. The Ives and Watson families were both friendly with the Lincolns and shared their political views. Lincoln is said to have enjoyed the macaroon pyramids baked in the Watson sweet shop. The oldest Watson son, Ben, was an early booster of Lincoln, and a neighbor who helped renovate the one-story cottage on Jackson and Eighth into the iconic Lincoln family residence: a two-story house with a kitchen, two parlors, and a dining room. The Ives family also lived nearby, about one block away from the Lincoln home on the north side of Market (later Capitol) Street. The rooms and space above Ives and Curran, which included the residential quarters of Isaac Curran, served as a political watering hole for Republicans, hosting community socials whose attendees included Mary Todd Lincoln.

When Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860, he was accompanied on his train trip east by Abigail’s older brother Ben. Abigail handcrafted a U.S. flag with thirty-one stars, the last for California, that decorated the engine of the train. Abigail Ives treasured a rare photograph of the Great Emancipator from these days; eventually, like many Welles talismans, it would end up in the hands of Dr. Maurice Bernstein.

Abigail Ives served admirably on the board of the Springfield Soldiers Aid Society, assisting Civil War soldiers before and after the war. The Ives family saw itself as playing an active role in history, and she and John passed on the Lincolnesque tradition of good citizenship to their one daughter and three sons.

Orson’s maternal great-grandfather led “a quiet tick-tock, tick-tock existence,” in the words of Lincoln’s biographer, the poet Carl Sandburg, “and looked like a clock of a man.” John G. Ives’s progress toward prosperity was also metronomic. Beyond his jewelry and silverware shop, Ives dabbled profitably in the coal and grain markets, and he became a leader of the Springfield branch of the Republican Party. Twice he served as treasurer of Sangamon County, “elected on the Republican ticket against a usual Democratic majority of several hundred,” according to a local history, and twice he was voted onto the county board of supervisors.

The youngest of the Ives children, Benjamin, was born in 1850. He worked for his father as a notary and accountant, and in 1876, when he was still living under his parents’ roof, married a woman ten years his junior. No older than seventeen when she married, Lucy Alma Walker was a Springfield native from a farming family; not until she bore her first child did the couple move into their own home on South Seventh Street. Though accounts vary, the baby girl was most likely born on September 1, 1883. Her parents named her Beatrice Lucy, although as an adult Beatrice would rarely use her middle name.

The home where Beatrice Ives grew up was just a few blocks from the state capitol, hailed as one of the great buildings of the Midwest after its completion in 1889. One of her father’s boyhood playmates was his cousin William Weldon Watson III, who went on to marry a banker’s daughter named Augusta Crafts Tolman in an Illinois town called Kane in the county of Kane. Beatrice, too, would find many playmates amid her seemingly limitless Watson cousins.

Much of what we know about Beatrice’s girlhood was handed down by Dr. Bernstein, who adored her and filled in the gaps in her story with embellishments. Bernstein insisted that Beatrice as a young woman “rode horseback like a man,” and that she was a “splendid marksman” who engaged in regular target practice and country shooting, though “never at birds.” (Orson sometimes parroted this received version of events in interviews.) In Beatrice’s day and age people were raised close to the land, but such expertise was not as common among girls, and Beatrice’s poise and physical appearance—she was a tall young woman, people remembe

red, ladylike but with a strong chin, always smartly dressed—were part of her mystique.

Beatrice also had an unusually husky voice; newspapers later praised its musical lilt, and her son, Orson, finding the mot juste, likened it to a “cello” in tone. Even as a teenager, Beatrice was recognized as something of a musical prodigy. Musicianship ran in the family: her mother, Lucy, played piano, as did her aunt Augusta, who had been a recitalist, and who encouraged her own progeny to dedicate themselves to artistic self-expression through art and music. Like her aunt, with whom she was close, Beatrice would favor classical over popular music; though she would oblige partygoers with a Sousa march, delivering the straightforward music with a smile and a flourish, she preferred to challenge herself with complex piano pieces.

One photograph of the beautiful and intelligent young Beatrice, seated at her piano, suggests a sweeter, more vulnerable side to her strong personality. By the time the photo was taken, her father, Benjamin Ives, had found a business foothold in Chicago, making regular trips there to promote his Illinois Fuel Company, with stock capitalized at $1.5 million—most of the stock his—and mines in Minnesota and in Sangamon County, where Springfield was located. Ives doted on his promising daughter, who soon set her sights on attending a fine arts academy in the city.

After Beatrice finished secondary school in Springfield—probably at the Academy of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, the Catholic girls’ school—she and her mother joined the head of the family in Chicago. The Iveses found a flat in the Hyde Park area. Beatrice enrolled in the Chicago Conservatory, the city’s most reputable school of music and dramatic arts, located in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s monumental Auditorium Building, touted as the tallest and largest building in America when it opened in 1889.

Beatrice took private tutoring from a Russian Lithuanian–born former child prodigy, Leopold Godowsky, then at his peak as a prolific composer of daunting virtuoso piano pieces. An eclectic teacher who inspired loyalty among his many students, Godowsky was a champion of Chopin, Bach, Haydn, and Mozart, and a performer of impeccable technique whose novel percussionist approach relied on weight release and relaxation rather than muscular impetus. Beatrice basked in his guidance, and under his eye her technical playing developed emotional expressiveness, alternating power with delicacy and feeling. She also studied music theory under the German-born Adolf Weidig, an authority on theories of composition and harmony, citing his influence in her publicity materials later in life.

Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane

Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane